2 Package manager

In general a package manager (or package-management system) is a tool that automates the process of:

- installing,

- upgrading,

- configuring,

- removing,

- …

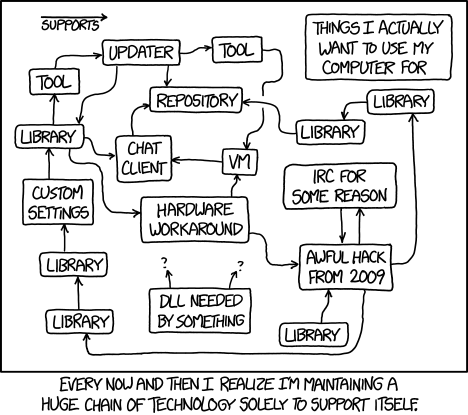

for computer programs, software libraries, general data, or other tasks. We all use package managers on our smart phones or computers. They come in various forms and accessibility like the GUIs Google Play, App Store, Microsoft Store, but also in terminal form as apt, dnf, zypper, homebrew, and many more. Most of these tools give us an easy way to work with some application without needing to know much about how the software is built. Especially in our modern infrastructure, were a build process can easily start looking very similar to this:

The same is true if we change perspective, from a user installing software to an engineer designing software.

Back in the days, and often still for some languages, you manually had to integrate some library you wanted to use and they often came with elaborate build scripts (with their own dependencies, … insert recursion here). Especially cumbersome were problems where you needed different versions of the same library for different projects. Nowadays, this task is performed by package managers to the relief of developers everywhere. If you have a good package manager you do not realize the burden it takes of your shoulders. It is worth highlighting, that a good package manager can define the difference between a successful programming language and a footnote in the index of programming languages.

While it would be worthwhile to visit the various ways and strategies these systems take, we will focus on systems for python.

2.1 Package management for python

Before we go into detail for the package manager of choice, we need to discuss what such a system is supposed to offer us.

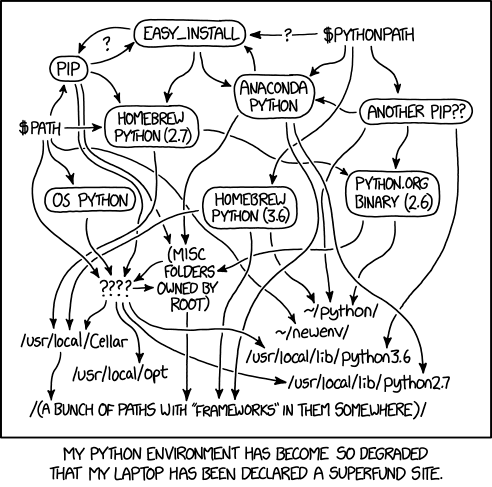

As a starting point have a look at what xkcd has to say about it:

Please think about what you believe are must have and nice to have features that we should have for our package manager.

Here is the (probably not complete) authors list (random order):

- must haves

- nice to haves

- multiple sources for packages

- private repos (work environment)

- stay close to official PEP standards 1

- backwards compatibility for lock files

- easy way to have a project version

- local install for self written packages

- different algorithms for building the dependency tree

- deployment with testing capabilities

- integrate with virtualization

- compatibility to other package managers

- allow integration of environment variables, e.g.

.envfiles

- multiple sources for packages

- obvious

- integrate with version control software

- provide a wide range of packages

- have a good user interface

The Python Packaging Authority (PyPA)2 provides a user guide for distributing and installing Python packages. As soon as you think of providing your own package for others you should carefully study this guide, but for now, we only have a quick look into Tool recommendations.

The Python packaging landscape consists of many different tools. For many tasks, the Python Packaging Authority (PyPA, the working group which encompasses many packaging tools and maintains this guide) purposefully does not make a blanket recommendation; for example, the reason there are many build backends is that the landscape was opened up in order to enable the development of new backends serving certain users’ needs better than the previously unique backend,

setuptools. This guide does point to some tools that are widely recognized, and also makes some recommendations of tools that you should not use because they are deprecated or insecure.Source: From the PyPa Guide, as of 9th of September 2024

The standard tool is pip and for scientific software specifically conda and Spack.

We are going to look at pdm (see Ming (2019)), as this is a modern Python package manager that uses pyproject.toml files to store metadata of the project and much more.

The main thought behind selecting pdm for further discussions here is the experience of the authors regarding cross platform support, ease of use, and transferability to other languages like julia, rust, or go. Especially the Pgk.jl package in julia was such a drastic contrast to conda that the authors searched for an alternative.

2.2 An introduction on working with PDM for your python project

PDM can manage virtual environments (venvs) in both project and centralized locations, similar to

Pipenv. It reads project metadata from a standardizedpyproject.tomlfile and supportslockfiles. Users can add additional functionality through plugins, which can be shared by uploading them as distributions.Unlike Poetry and Hatch, PDM is not limited to a specific build backend; users have the freedom to choose any build backend they prefer.

Source: From the pdm-project on github, as of 9th of September 2024

The following screen cast gives us a quick overview of its capabilities.

For this guide we closely follow the notes on the project page https://pdm-project.org/, please note that the original code and potential updates to it can be found there, see Ming (2019).

2.2.1 Installation

First we need to install pdm so that it is available (globally) on our system. For this to work, Python version 3.8 or later must be available on the system.

The recommended way is to use the provided install script.

curl -sSL https://pdm-project.org/install-pdm.py | python3 -(Invoke-WebRequest -Uri https://pdm-project.org/install-pdm.py -UseBasicParsing).Content | py -Of course we do not just download a file from the internet without checking the content. At the time of writing the current sha256 is

cdaae475a16ae781e06c7211c7b075df1b508470b0dc144bbb73acf9a8389f91 install-pdm.pyYou can check the file sha by calling:

curl -sSL https://pdm-project.org/install-pdm.py | shasum -a 256Get-FileHash -InputStream (Invoke-WebRequest -Uri https://pdm-project.org/install-pdm.py -UseBasicParsing).RawContentStream -Algorithm SHA256By default, pdm is installed into the user space (depending on the platform), but this can be modified via arguments to the script, see the help option of the script.

2.2.1.1 Optional - Shell completion

For a better user experience we would recommend to include the shell completion.

pdm completion bash > /etc/bash_completion.d/pdm.bash-completion# Make sure ~/.zfunc is added to fpath, before compinit.

pdm completion zsh > ~/.zfunc/_pdm# Create a directory to store completion scripts

mkdir $PROFILE\..\Completions

echo @'

Get-ChildItem "$PROFILE\..\Completions\" | ForEach-Object {

. $_.FullName

}

'@ | Out-File -Append -Encoding utf8 $PROFILE

# Generate script

Set-ExecutionPolicy Unrestricted -Scope CurrentUser

pdm completion powershell | Out-File -Encoding utf8 $PROFILE\..\Completions\pdm_completion.ps12.2.2 Start a new project

Let us start a new project in a new directory:

- 1

- create a directory

- 2

- change into this directory

In order to start a new pdm project you can use pdm init. This will prompt you with a couple of questions and based on the answers the pyproject.toml file is initialized.

1$ pdm init

Creating a pyproject.toml for PDM...

2Please enter the Python interpreter to use

0. cpython@3.11 (/usr/local/bin/python3)

1. cpython@3.12 (/usr/bin/python3.12)

2. cpython@3.11 (/usr/local/bin/python3.11)

3. cpython@3.8 (/usr/local/bin/python3.8)

Please select (0): 1

3Virtualenv is created successfully at /tmp/test/.venv

4Project name (test):

5Project version (0.1.0):

6Do you want to build this project for distribution(such as wheel)?

If yes, it will be installed by default when running `pdm install`. [y/n] (n): n

7License(SPDX name) (MIT):

8Author name (John Doe):

Author email (John.Doe@generic.edu):

9Python requires('*' to allow any) (==3.12.*):

Project is initialized successfully- 1

-

Start the initialization with

pdm init. - 2

-

We need to select a python interpreter.

pdmwill search for all available interpreters on your path, if you need a different version than those available you can usepdmto install a new standalonepythonversion, seepdm pythoncommand or the docs3. - 3

-

By default

pdmwill create a newvirtualenvfor you as this is the recommend procedure, if you want to influence this behavior see docs. - 4

-

We need to specify a project name. This name is used in the

pyproject.tomlandpdmwill also generate asrc/<name>directory for you right away (together with atestdirectory).pdmuses its default template, see docs. - 5

-

The version of your project needs to be initialized.

pdmfollows semantic versioning4 by default. If you do not have a specific version in mind stick to0.1.0for a new project. - 6

-

Next we need to decide if we plan to distribute the project. For now

n(no) will suffice, but hopefully by the end of these notes you feel comfortable enough to release your own package. Once this is the case, take a look at the docs and the Python Packaging User Guide. - 7

- Licensing is next. This is a rather important issue when you release software, but we need to postpone it as well. So stick to the default for now.

- 8

-

Author name and email can (and should) be a list if you have multiple contributors.

pdmwill try to figure out defaults from system settings. - 9

-

Finally, you will be asked for the required python version. Here you can specify the compatibility of your project to various python versions5. For good reason, by default it will only allow the current version you selected in the first step. In theory you can specify something like

>=3.8,!=3.9.0,<3.13(a python version between 3.8 and 3.13, including 3.8 but excluding 3.13 and additionally excluding 3.9.0) but be aware that might become tricky when adding dependencies.

Now you have a new project available and it should look like this:

1$ tree -a

.

2├── .gitignore

├── .pdm-python

├── __pycache__

├── pyproject.toml

├── README.md

├── src

│ └── test

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── __pycache__

├── tests

│ ├── __init__.py

│ └── __pycache__

3└── .venv

├── bin

│ ├── activate

│ ├── activate.csh

│ ├── activate.fish

│ ├── activate.nu

4 │ ├── activate.ps1

│ ├── activate_this.py

│ ├── python -> /usr/bin/python3.12

│ ├── python3 -> python

│ └── python3.12 -> python

├── .gitignore

├── lib

│ └── python3.12

│ └── site-packages

│ ├── _virtualenv.pth

│ └── _virtualenv.py

└── pyvenv.cfg

12 directories, 19 files- 1

- List all files in the directory

- 2

-

A

.gitignorefile is created - 3

- Virtual environment

- 4

- Windows activation start file (cross platform)

The second highlighted section tells us that pdm is designed to work with a version control system. By default it uses git as seen by the .gitignore file highlighted. In this context:

You must commit the pyproject.toml file. You should commit the pdm.lock and pdm.toml file. Do not commit the .pdm-python file.6

To check what setup pdm created for you, you can use the pdm info command, where the --env option provides us with more details about the environment/platform.

$ pdm info

PDM version:

2.18.1

Python Interpreter:

/tmp/test/.venv/bin/python (3.12)

Project Root:

/tmp/test

Local Packages:

$ pdm info --env

{

"implementation_name": "cpython",

"implementation_version": "3.12.3",

"os_name": "posix",

"platform_machine": "x86_64",

"platform_release": "6.8.0-41-generic",

"platform_system": "Linux",

"platform_version": "#41-Ubuntu SMP PREEMPT_DYNAMIC Fri Aug 2 20:41:06 UTC 2024",

"python_full_version": "3.12.3",

"platform_python_implementation": "CPython",

"python_version": "3.12",

"sys_platform": "linux"

}Of course it is also possible to import from other package manager systems, see docs.

2.2.3 Manage dependencies

Now that the project exists we can look at the main task: managing packages. We will cover the basics that we need, for a full guide see Manage Dependencies at docs.

2.2.3.1 Add dependencies

To add a dependency you can use the pdm add command, where the system follows the PEP 508 specifications.

pdm add requests # add requests

pdm add requests==2.25.1 # add requests with version constraint

pdm add requests[socks] # add requests with extra dependency

pdm add "flask>=1.0" flask-sqlalchemy # add multiple dependencies with different specifiersIt is rather common for python dependencies to have dependencies on their own. pdm will make sure to install all of those as well. Everything that is installed will end up in the pdm.lock file with the exact version and where it comes from.

In contrast to other dependency management systems such as requirements.txt a very handy feature of pdm is that it will only add the specified dependencies to the pyproject.toml and not all sub-dependencies. This makes it easier for somebody else to keep track of what your actual dependencies are and especially for update procedures.

2.2.3.1.1 Add local dependencies

Quite often it happens that you develop a project and use it as a dependency in another project you are working on. In this case you want to have a local dependency. This can be added by calling:

pdm add ./my-projectIt is important to mention, that the path must start with . otherwise it is not interpreted as a local dependency.

2.2.3.2 Development dependencies

With pdm you can also define groups of dependencies that are particularly useful during development. This might be a linter, formatter, or tools for testing and creating the docs.

pdm add -dG lint flake8You will find these dependencies in a special section in you pyproject.toml file, namely:

[tool.pdm.dev-dependencies]

lint = ["flake8"]2.2.3.3 Inspect dependencies

If you need to find out what your installed dependencies are you can use pdm list or pdm list --tree.

$ pdm list --tree

requests 2.32.3 [ required: >=2.32.3 ]

├── certifi 2024.8.30 [ required: >=2017.4.17 ]

├── charset-normalizer 3.3.2 [ required: <4,>=2 ]

├── idna 3.8 [ required: <4,>=2.5 ]

└── urllib3 2.2.2 [ required: <3,>=1.21.1 ]2.2.3.4 Update dependencies

If you find that a package has released an update that is required for your project you can use pdm to update your packages:

pdm updatewill update all packages (if possible) in your pdm.lock file, while

pdm update requestswill only update the specified dependency (you can specify multiple packages).

2.2.3.5 Remove dependencies

If you have added a dependency but no longer need it, you can remove it by calling pdm remove. Note that all sub-dependencies will be removed as well.

2.2.3.6 List outdated dependencies

With pdm outdated you get a list of outdated packages with the latest version available.

2.2.3.7 Other dependencies than python packages

It might happen that your project needs additional dependencies other than python resources. In this case you can also use pdm to install a multitude of those.

As an example, you can install the Intel Math Kernel Library (mkl) and cmake by calling

pdm add mkl cmake2.2.4 Initialize an existing project

If the pdm project already exists, e.g. you just cloned a project, all you need to do is run

pdm installto check the project file for changes, update the lock file if needed and run pdm sync to install all packages from the lock file.

2.2.5 Running your code

As mentioned throughout these notes, pdm uses virtualenv to manage your project. This means you need to activate the project to work with it.

If you simply want to run a python script in your environment use:

pdm run python <SCRIPT.py> <arguments>Similar you can start the python console via:

pdm run pythonIf you need to work in your current terminal with the environment you created it is easier to use pdm venv activate which will tell you how to activate the enviroment in your current terminal. In bash you can use

eval $(pdm venv activate)to directly activate the environment.

You should set up your IDE such that it searches for .venv directories for the python interpreter to make sure you do not get missing includes warnings and if you use the direct call or debug features you call the correct version.

This concludes our little guide for package managers in python. Make sure to revisit this sections and the pdm docs if you need them for the course of this section.

Short for Python Enhancement Proposals, see Python PEPs↩︎

The Python Packaging Authority (PyPA) is a working group that maintains a core set of software projects used in Python packaging, see https://www.pypa.io/ as at 9th of September 2024↩︎

In case you are wondering what the

.pdm-pythonfiles is, it stores the path to yourpythoninterpreter and is used for subsequent calls.↩︎We recommend having a read of semver.org↩︎

Python does not follow SemVer (see docs), sometimes a minor version will have a breaking change, so make sure to check the Porting to Python X.Y section for What’s new.↩︎

Quote from pdm-project.org as at 9th of September 2024↩︎