1 != 2

1 < 2

2 > 3

1.0 >= 1

0.99 <= 1

# and combine them with logical operators

(1.0 <= 1) and (1.0 >= 1)

(2 < 1) or (2 > 1)

not (1 != 2)1 Introduction to Python

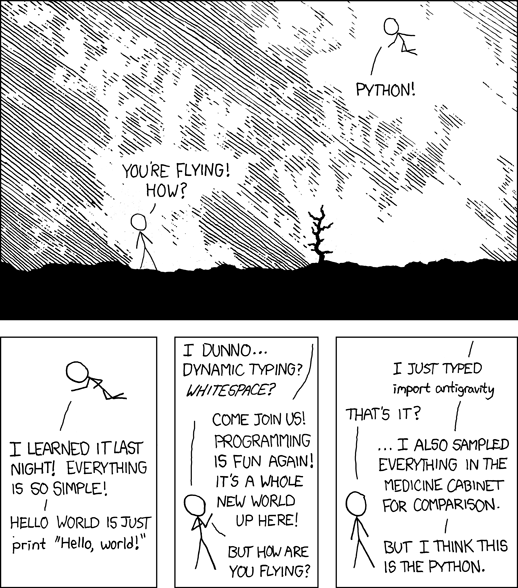

In these notes we will focus on Python as the programming language of choice. The main reason for this is that python is currently the language where a lot of programming for data science is happening. Other languages like Julia are catching up quick though. In general, Python is a very popular programming language. It currently ranks #2 in the Redmonk Rating.

This section is going to give a rough overview to get us started, but we are not going into much detail. We will focus on particular aspects of the language in later parts to get a more detailed look.

So let us start with a brief introduction and then get into programming, as usually there is no better way to learn a language than using it. Python has the reputation of being easy to learn, even though not always straight forward.

Python is a so called high-level1 programming language that was designed with an emphasis on readability2 in mind. It was developed by Guido van Rossum in the late 80s and the first release of version 0.9.0 to the public came in 1991. Subsequently, in October 2000 Python 2.0 and in 2008 Python 3.0 were released. There are currently multiple supported versions of Python available, of which 3.12.63 is the latest stable release, see Wikipedia for the history of Python.

In these notes we will focus on Python 3.12.

Python does not follow Semantic Versioning4, see python docs), sometimes a minor version will have a breaking change, so make sure to check the Porting to Python X.Y section for What’s new if included code is no longer working.

With regards to style, Python combines imperative , object oriented, and functional programming paradigms (more on that later). Furthermore, it is available for all major (and minor) computing platforms and there is an ever growing library of additional packages that can be loaded to extend the base functionality. This allows you to write highly complex programs with a few lines of code.

Python is an interpreted language, meaning that the code you write is not compiled to machine code (like in C/C++ or Fortran) but rather interpreted/executed by an (appropriately named) interpreter. This allows you to write a program interactively (in the Python REPL5) or provide the interpreter with a script file that is processed one line after the other. These files usually have the ending .py. The interpreter and the language are most of the time both called Python.

Like all programming languages, Python has a certain syntax that we need to follow otherwise the interpreter can not execute the code, this is similar to grammar in a language like English. The big difference (which probably cannot be avoided in these notes) is that we can still understand an English text if it is full of grammar mistakes, spelling errors or plain typos. Python will not give you that much leeway, but some.

There is still some room to wriggle around but it is best if you hold yourself to the Style guide - PEP 8 right from the start (we will do so in these notes, if not open an issue on GitHub, Link on the right below the section index).

Installation

On Linux and Mac a recent Python version is usually installed. Check this by opening a terminal and running

$ python3 --version

Python 3.12.3and you should see something similar if not the same. If not have a look here and search for your platform.

For Windows 10 and above we can use the version from the Microsoft Store. If you have another version check here too and search for your platform.

1.1 Getting started

As usual for programming guides, we start with:

print("Hello, World")Hello, WorldThese notes are generated from markdown and executable code (for a lot of the Python aspects). This means sometimes the results are part of the text, but if we need to make sure you can see the output we highlight it with some background color. For this reason and to make it easier to copy and past code from the notes we omit >>> that you see in your REPL.

Lets break down what we did above6:

- we called a function

print- indicated by(and)respectively, - we handed the text Hello, World to that function - indicated by the two

", - the REPL returned the result and printed it on screen.

The text above is called a string and you can do operations with strings, like:

print("Hello," + "World")

print("Spam" * 5)Hello,World

SpamSpamSpamSpamSpamHere + and * are so called operators. The first combines (concatenates) two strings, the second multiplies one string.

The Style guide - PEP 8 tells us that an operator should have a leading and trailing white space.

In case we want to know more about the function print we can use another function to get some more insight:

help(print)Help on built-in function print in module builtins:

print(*args, sep=' ', end='\n', file=None, flush=False)

Prints the values to a stream, or to sys.stdout by default.

sep

string inserted between values, default a space.

end

string appended after the last value, default a newline.

file

a file-like object (stream); defaults to the current sys.stdout.

flush

whether to forcibly flush the stream.

Now let us pick up a bit of speed.

- 1

-

We can write comments, that get ignored by the interpreter. They start with

# - 2

- Comments can also follow a command

544If you copy and execute the code above your output will differ and look something like:

>>> # Mathematical operators

>>> 3 + 2

5

>>> 2 * 10

20

>>> 4 // 2

2

>>> 4.0 / 2

2.0

>>> (9 + 8) * 32

544This is due to the fact that the system used to create these notes does not feed the input to the REPL one by one but rather as a script. Therefore, we will often just suppress the output or if we want to make sure something is printed in the notes we will use print explicitly.

There are the usual boolean operators for comparison:

We can assign a value to a variable and use them later on:

pi = 3.1415926535897932

x = 90

# Convert degree to radiant

x_rad = x * (pi / 180)

# Convert it back to degree

x_new = x_rad * (180 / pi)

# Check if they are the same

x == x_newWe can also change the value of a variable:

# We can make the printed statement more elaborate

print("x =", x)

x = 45.0

print(f"x = {x}")

print(f"{x = }")x = 90

x = 45.0

x = 45.0Python is dynamically typed, meaning that the type of a variable is checked during runtime and not beforehand.

As a result you can change the type7 of a variable without the interpreter complaining about it. This is often the cause of strange bugs in programs so be aware that Python has types, even though we do not always see them.

We have simple simple control sequences that help us to run different code depending on a condition:

if x < 90:

x = x * 2 # This section gets executed if the statement is true

else:

x = x / 2 # And this if it is false

print(f"x = {x}")

if x < 45:

x = x * 2

elif x < 90:

x = x * 3 # If the first statement is false but the second true

else:

x = x**2 # If none of the above statements is true

print(f"x = {x}")x = 90.0

x = 8100.0In order to understand loops better we first need to introduce lists. In essence, they represent an ordered sequence of values that can have arbitrary types.

# List of integers

[2, 4, 6, 8]

# List of strings

["A", "B", "C"]

# List of lists

[[2, 4, 6, 8], ["A", "B", "C"]]

# List of mixed types

[2, "A"]

# Assign a list to a variable

integers = [2, 4, 6, 8]

# Changing values

integers[1] = -4

# append something to a list

integers.append(10)

# combine to lists

integers + [1, 3]There are also functions that can generate specific types of lists for you. One such function is range, with the signature range(start, stop[, step]).

# List of integers from 0 to 2

range(3)

# List of integers from 5 to 9

range(5, 10)

# List of integers from 10 to 1 in reverse order

range(10, 0, -1)range(10, 0, -1)Note that the stop value is not part of the list but rather stop -1 and technically range does not return a list but rather an object that behaves like a list for most parts.

# Part of the help

>>> help(range)

Help on class range in module builtins:

class range(object)

| range(stop) -> range object

| range(start, stop[, step]) -> range object

|

| Return an object that produces a sequence of integers from start (inclusive)

| to stop (exclusive) by step. range(i, j) produces i, i+1, i+2, ..., j-1.

| start defaults to 0, and stop is omitted! range(4) produces 0, 1, 2, 3.

| These are exactly the valid indices for a list of 4 elements.

| When step is given, it specifies the increment (or decrement).Now let us introduce loops as part of our control sequences:

# For loops work best with lists or sets

sum = 0

for i in integers:

sum = sum + i

mean = sum / len(integers) # len computes the length of a list

print(mean)

# Find out how many even and how many odd number are in a list

odd = 0

even = 0

for i in range(1, 10):

if i % 2:

odd = odd + 1

else:

even = even + 1

print(f"{even = }, {odd = }")

# While loops run until a statement is no longer true

a = 5

b = 2

c = 1

while a > 0:

a = a - 1

c = c * b

print(f"{b}^5 = {c}")4.4

even = 4, odd = 5

2^5 = 32There is an internal function called sum and we just overwrote this function, so be careful how you choose your variable names.

Of course there are easier ways to compute the sum of a list or \(2^5\). For this we need to import additional functions:

import math

mean = math.fsum(integers) / len(integers)

print(mean)

c = math.pow(2, 5)

print(c)4.4

32.0math is one of the Python standard libraries, but quite often they do not suffice for the task at hand and you need some additional libraries.

In the next section we will discuss package managers and one possible solution for this.

Furthermore, so far we only typed in the REPL and if we want to do the same again we need to retype everything. So we need to talk about script files which will lead us to version control.

For now, this ends our brief start with Python but you should try our new knowledge by finishing the following exercise.

1.2 Exercises

A language that has a strong abstraction level between the hardware of the computer and the user.↩︎

The term describes how easy it is for a human reader to follow the purpose, control flow and the single operations of source code, i.e. a program.↩︎

As of September 6th 2024, see Python Source Releases for a current overview.↩︎

A way of specifying what the usual three numbers of a version mean, see semver.org↩︎

Read Evaluate Print Loop↩︎

We start easy and with a bit more explanation, but do not worry we will not always break it down as much.↩︎

Type could be something like integer, float, or string↩︎